Don't expect instant gratification in the race to recover wreckage from the missing Malaysia Airlines jet, even if searchers confirm they're hearing pings from the Boeing 777's black box.

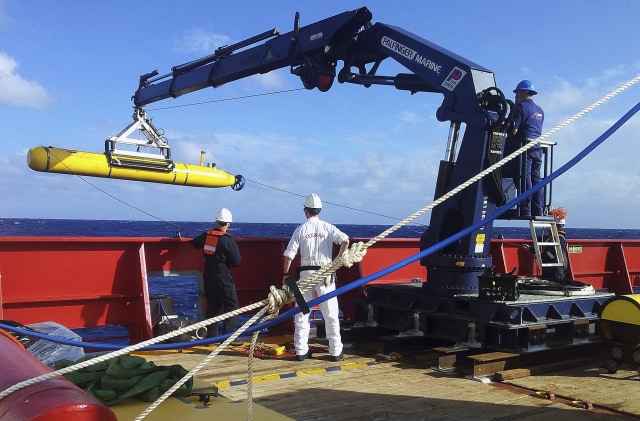

The operation won't be like the thrill-a-minute treasure hunt in the movie "Titanic": Identifying the wreckage will require painstaking passes by a torpedo-like autonomous robot called Bluefin 21, which will be operating at the very limit of its range.

If the side-scan sonar readings identify a field of debris, the robot sub will go over the territory again with high-resolution video cameras, pinpointing the locations of the black-box recorders and other evidence.

It's only after those clues have been collected that searchers can send down yet another kind of robot, connected to a search ship and capable of bringing debris up to the surface.

The first part of the task will require programming the Bluefin 21 in advance to look for something the size of a shoebox in a search area that could span hundreds of square miles.

'"Anytime you're trying to find something that small in an area that large, it is going to be exceedingly complicated and difficult," Chris Johnson, spokesman for the U.S. Naval Sea Systems Command, told NBC News. "It takes a huge amount of patience. This is one of the most difficult things the Navy does."

Job 1: Confirming the pings

The U.S. Navy has contracted with Maryland-based Phoenix International Holdings to lend underwater assets to the international search, operating from the Australian ship Ocean Shield. Phoenix has played a lead role in searches for sunken debris ranging from a Civil War ship to real-life surveys of the Titanic shipwreck to the Air France jet that was lost in 2009.

Johnson said the estimated cost of the Navy-Phoenix operation is $3.6 million, which covers transporting and operating the Bluefin 21 as well as a device that picked up what could be black-box pings.

The device, known as a towed pinger locator, was dragged behind the Ocean Shield over an area of the Indian Ocean roughly 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) west of Perth, Australia. The locator detected pulsed signals on the right frequency for the black boxes, for as much as two hours at a time. Detection equipment aboard a Chinese ship reportedly picked up the signals as well.

"The new developments over the last few hours have been the most promising lead we have had," Malaysian Transport Minister Hishamuddin Hussein told reporters in Kuala Lumpur on Monday. He spoke nearly a month after Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 disappeared on March 8, as it flew from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing with 239 people aboard.

Robo-sub ready to go

If the go-ahead is given by the Joint Agency Coordination Center in Perth — the headquarters for the international search — the Bluefin 21 would begin a pre-programmed survey of the seafloor.

One of the Bluefin 21's most recent claims to fame was its role in the search for wreckage from Amelia Earhart's airplane, which disappeared in the Pacific in 1937.

A Bluefin 21 autonomous underwater vehicle is hoisted back onboard the Australian ship Ocean Shield after a successful buoyancy test in the southern Indian Ocean on April 4.

The 16-foot-long (5-meter-long) robot, built by Massachusetts-based Bluefin Robotics, is built for surveys that go as deep as 2.8 miles (4,500 meters). That's just about how far down the seafloor is in the Indian Ocean search area.

Searchers typically program the propeller-driven robo-sub with the coordinates for a back-and-forth search that's been compared to mowing a lawn. First, the vehicle will survey the area with side-scan sonar. It can stay underwater for 25 hours at a time, and cover up to 40 square miles in the course of a day, Johnson said. The sonar readings are stored in the robot's removable memory, and retrieved once the sub comes back up topside.

If the sonar scan turns up objects of interest, the Bluefin 21 would be refitted with high-resolution cameras for a visual survey. The robot would have to dive closer to the seafloor for a concentrated survey of the target area. When the imagery is brought back up, analysts would pore over the pictures, looking for the shoebox-sized cockpit voice recorder and flight data recorder.

We're going to need another robot

Assuming the black boxes and other wreckage are identified, what comes next? That would be up to the Joint Agency Coordination Center.

"We don't know what the next step would be," Johnson said. "Presumably an ROV would be what you'd need to get debris off the seafloor."

ROVs — that is, remotely operated vehicles — are equipped with arms and claws to pick up debris and bring it up to the surface. Unlike the Bluefin 21 and other autonomous robots, ROVs have a real-time connection with their operators for communication and control.

Several ventures around the world manufacture ROVs capable of working at depths of 3 miles and beyond. But if Phoenix is involved in the operation, it will almost certainly use its Remora 6000 ROV, which is rated to a depth of 3.7 miles (6,000 meters).

A Remora 6000 remotely operated vehicle is hoisted up from the Atlantic Ocean with the cockpit voice recorder from Air France Flight 447 in 2011.

The Remora 6000 came into play during the recovery of Air France wreckage and the inspection of Titanic wreckage in 2011. Weeks or months from now, the ROV could well become the star of the show once more.

But that star turn would come long after the pings from the Malaysia Airlines jet have faded to silence. That's what makes the next couple of days so crucial: If the ping detections are confirmed, that will at least give the robots a realistic area to search.

It's by no means a slam dunk, but Phoenix International's operators are accustomed to long, grueling searches. After all, it took them two years to locate and recover the Air France wreckage.

TO WATCH VIDEOS CLICK HERE